Introducing the Hutong

Hutongs are narrow streets or alley ways which represent an important cultural element of Beijing. In Beijing, hutongs are alleys formed by lines of Siheyuan, traditional courtyard house. Many neighborhoods were formed by joining one Siheyuan to another to form a hutong, and then joining one hutong to another which still form the heart of Old Beijing. The word hutong is also used to refer to such neighborhoods. Thanks to Beijing’s long history and status as capital for six dynasties, almost every hutong has its anecdotes, and some are even associated with historic events. In contrast to the court life and elite culture represented by the Forbidden City and Summer Palace, the hutongs reflect the culture of grassroots Beijingers. Since the mid-20th century, the number of Beijing hutongs has dropped dramatically as they are demolished to make way for new roads and buildings. More recently, some hutongs have been designated as protected areas in an attempt to preserve this aspect of Chinese cultural history.

Origin of name:

Version 1: The term “hutong” appeared first during the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368), and is a term of Mongolian origin meaning “water well”.

Version 2: Appeared first during the Yuan Dynasty, means “small alleys”.

Version 3: Appeared first during the Yuan Dynasty, means “town”.

Hisotry

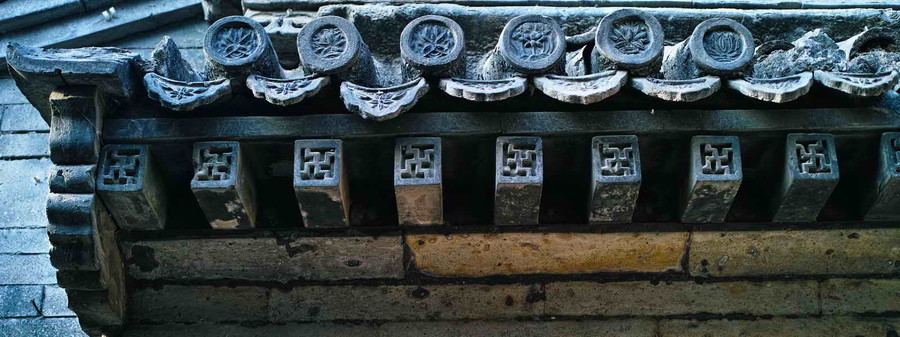

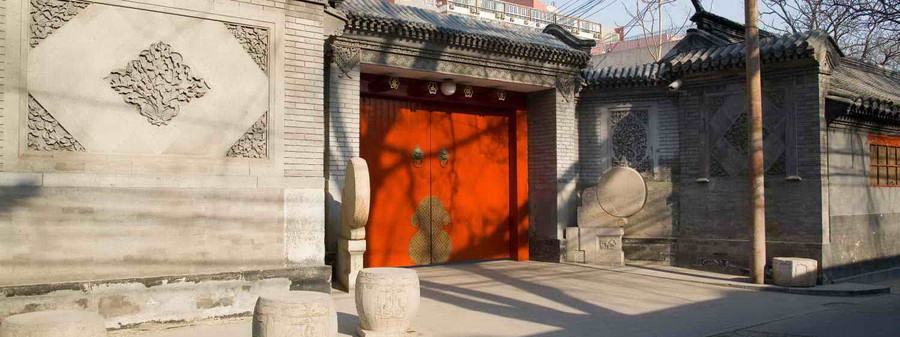

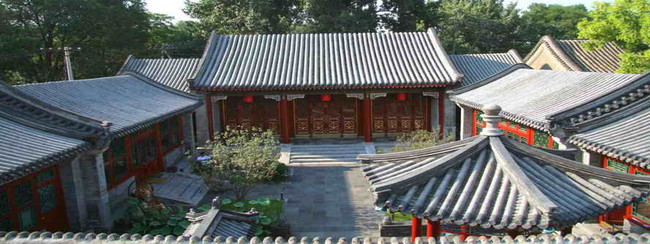

During China’s dynastic age, emperors planned the city of Beijing and arranged the residential areas according to the social classes of the Zhou Dynasty (1027 - 256 BC). In the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) the center of Beiing was the Forbidden City, surrounded in concentric circles by the Inner City and Outer City. Citizens of higher social status were permitted to live closer to the center of the circles. Aristocrats lived to the east and west of the imperial palace. The large Siheyuan (Quadrangle Courtyard) of these high-ranking officials and wealthy merchants often featured beautifully carved and painted roof beams, pillars and carefully landscaped gardens. The hutongs they formed were orderly, lined by spacious homes and walled gardens. Farther from the Forbidden City, and to its north and south, were residences of the commoners, merchants, artisans, and laborers. Their Siheyuan were much smaller in scale, simpler in design and decoration, hutongs were narrower as well. Almost all Siheyuan had their main buildings and gates facing south for more sunshine; thus most of hutongs run from east to west. Between the main hutongs, many tiny lanes ran north and south for convenient transportation

Historically, a hutong was also once used as the lowest level of administrative divisions in China, as in the Paifang system: the largest division within a city in ancient China was a Fang, equivalent to current day district. Each fang was enclosed by walls or fences, and the gates of these enclosures were shut and guarded in the evening, like a modern gated community. Each fang was further divided into several Pai, which is equivalent to a current day community. Each Pai, in turn, contained an area including several hutongs, and during the Ming Dynasty, Beijing was divided into a total of 36 Fangs.

Hutongs in the Modern Age

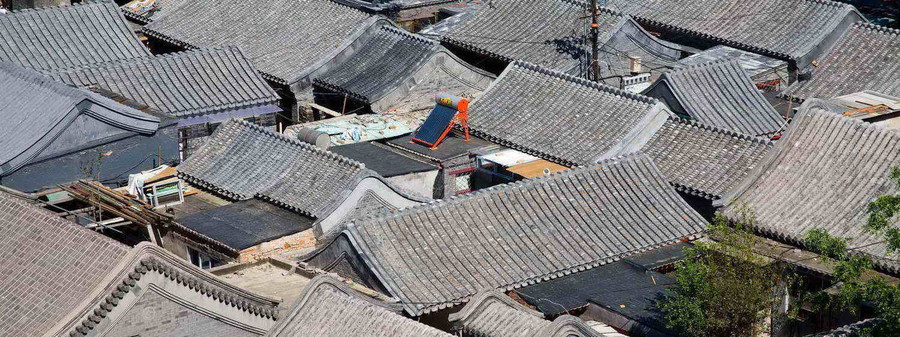

In the early 20th century, the Qing court was disintegrating as China’s dynastic era came to an end. The traditional arrangement of hutongs was also affected. Many new hutongs, built haphazardly and with no apparent plan, began to appear on the outskirts of the old city, while the old ones lost their former neat appearance. The social stratification of the residents also began to evaporate, reflecting the collapse of the feudal system. During the time of the Republic of China from 1911 to 1948, society was unstable, fraught with civil wars and repeated foreign invasions. Beijing deteriorated, and the conditions of the hutongs worsened. Siheyuans previously owned and occupied by single families were subdivided and shared by many households, with additions tacked on as needed, built with whatever materials were available. The 978 hutongs listed in Qing Dynasty records swelled to 1,330 by 1949. Following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many of the old hutongs of Beijing disappeared, replaced by wide boulevards and high rises. Many residents left the lanes where their families lived for generations for apartment buildings with modern amenities. However, many of Beijing’s ancient hutongs still survive and a number of them have been designated as protected areas, offering a glimpse of life in the capital city as it has been for generations. Many hutongs, hundreds years old, in the area of the Bell Tower, Drum Tower and Shichahai Lake are well-preserved amongst newly recreated versions, which are popular with tourists home and abroad.